Jet It joins Avantair as fractional failures, JetSuite’s $50 million in jet card losses, and millions of dollars lost by Aerovanti members.

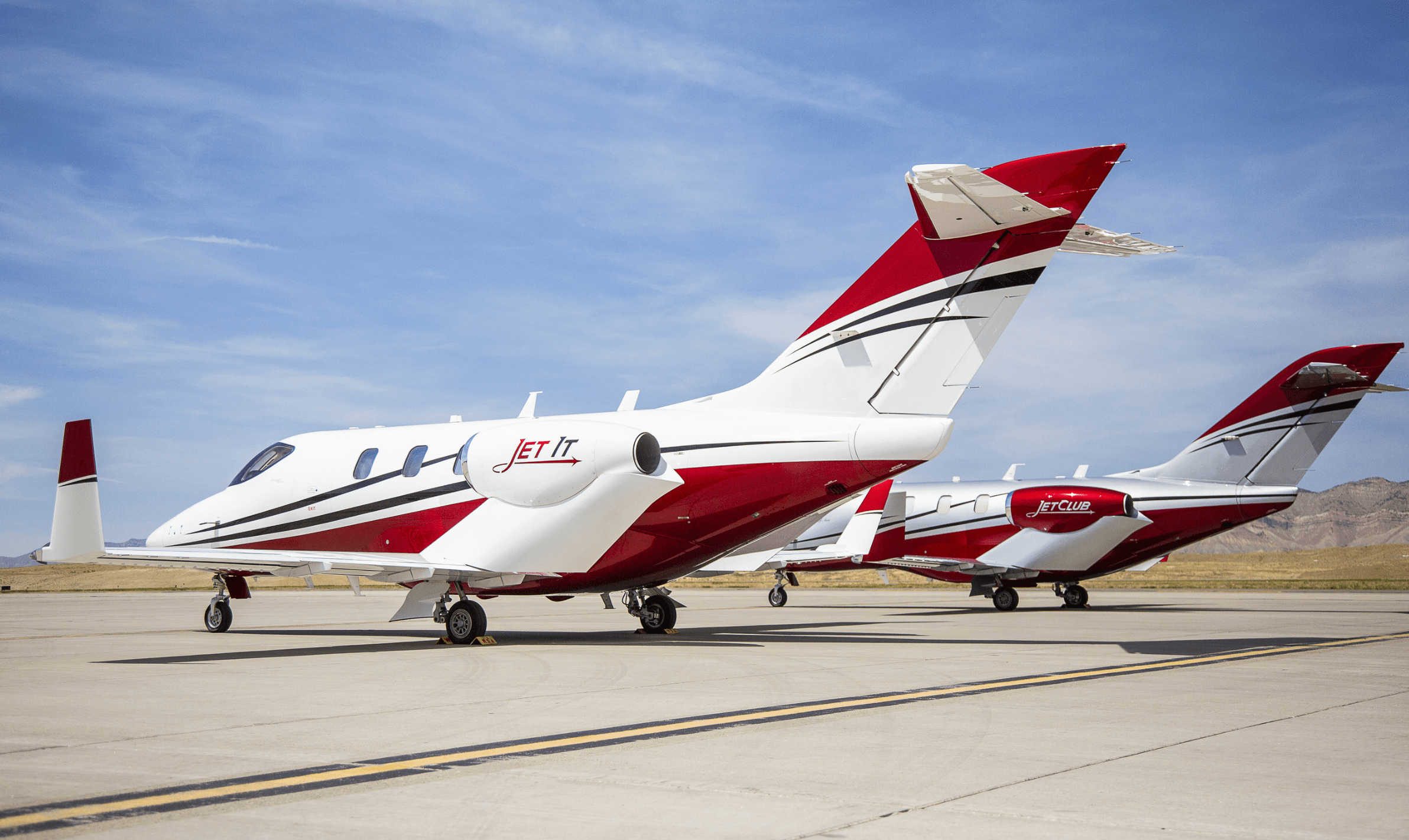

When the 2018 fractional startup Jet It shuttered in May 2023, it was among the 20 largest charter/fractional private jet operators in the U.S. The closure impacted over 150 share owners, revealed possible warnings for future buyers of private jet flight programs, and lessons that consumers can heed.

Private Jet Card Comparisons recently spoke to Amanda Applegate (pictured below), the seasoned business aviation attorney who represented 14 of Jet It’s owner groups for a behind-the-scenes look at what happened after the planes stopped flying.

We also asked her advice on how consumers can better protect themselves.

Applegate is no stranger to fractional ownership or provider failures.

A founding partner at Soar Aviation Law LLC, she specializes in private jet ownership, emphasizing fractional ownership due to her experience as Associate General Counsel and Vice President of NetJets Services, Inc., where she spent a dozen years with the company that pioneered fractional jet ownership.

She represented 25 Avantair fractional owner groups, comprised of nearly 300 fractional owners, following the 2013 grounding of its fleet and subsequent bankruptcy proceedings.

Applegate: We started getting notifications that the fleet was going to be grounded at the end of May. Then, from there, the planes never flew again under (Jet It’s) management. When that happened, people started googling what to do. My experience in unwinding another fractional ownership program, the Avantair matter, allowed a lot of those people to find me relatively quickly. Then, what often happens is you have one co-owner who owns shares in more than one aircraft. If I was being hired to represent one of the co-owner groups, and then one of the owners had to share on another plane, they would introduce me to that group. It spread pretty quickly.

Applegate: Yes. Using some of the systems that we have and resources we have, we went ahead and put together a co-owner list and a contact list for every single aircraft in the fleet so that we would be ready to respond if the owner groups reached out to us and wanted to engage us. We also collected the registration applications for each of the aircraft that showed who owned the aircraft and if Jet It owned any percentage of the aircraft. We had those sheets put together for 22 aircraft, and in the end, we ended up representing 14 of the owner groups. It does take some time to gather the signatures of each co-owner to make sure you fully represent the entire co-owner group.

Applegate: It was a pretty decent unwinding scenario as far as how the management at Jet It handled it because they did schedule a conference call with each of the co-owner groups and invited all of the co-owner groups to that. Then, they gave their perception of why things weren’t working out, and so they told the co-owners to do what they wanted with the aircraft. It did a couple of things. It put the co-owners in touch with one another. It helped them understand perhaps where their aircraft was.

Applegate: Yes. Jet It actually prepared a spreadsheet of the co-owners and their contact information for each of the aircraft and held a conference call with each of the co-owner groups. Using the list Jet It prepared, which was not 100% accurate, and the FAA registry records, we were able to quickly identify the co-owners. Then, after the Jet It call with each of the co-owners, we quickly had group calls (with the groups I represented) and made determinations as to what to do with each of the aircraft.

Applegate: We immediately retained a company to help us find the records and extract them from the location where they were stored. We pretty quickly got in and got all of the records for our co-owners out of there, and then we stored them in a safe location. The place where they were originally stored was a rented hangar space. Of course, if the rent maybe wasn’t paid on that space, then you have the risk of not being able to access those records. There was, I think, some misinformation about being locked out and some that were refusing entry and all of that. We learned from Honda that the programs on the aircraft were in default and worked to get the amount due so the programs could be reinstated.

Applegate: Certainly, we immediately wanted to get the records out, but the owner of the hangar was not in town. There was a delay because of that, but there wasn’t any desire to keep us out or restrict access. The hangar owner wanted the records out of their space as well, so there was sort of a mutual understanding that we could get them. We, of course, had to prove that we had the right to the records, and you want to make sure that that’s done (because) the aircraft is not going to be very valuable without the records. I appreciated that they wanted to make sure that we had the right to retrieve the records. Once we showed that (we represented the owners), we didn’t have any issues securing the records.

Applegate: Jet It and Honda (Aircraft Company) did help with the location of the aircraft, and we also used JetNet and FlightAware. It seemed as if there was a point in time in which those services were no longer tracking the Jet It fleet, which is something that I hadn’t experienced before. The last flight in JetNet, for example, wasn’t the last flight that the aircraft took. It took a little bit of time to figure out where the aircraft was located, and then once we did and got them, we had to determine, based on the majority of the co-owners, what we were going to do with the aircraft at that time.

READ: A Complete Guide to Fractional Ownership

Applegate: For each of the aircraft, the co-owners had to get together and decide what to do with the aircraft. All of my co-owner groups decided to sell the aircraft. We had one or two instances where one of the co-owners made an offer or, in fact, did purchase the whole aircraft by buying the other co-owners out.

Applegate: First, we had to determine how much was owed on the aircraft. If major maintenance events had just occurred, then those would have to be paid before you can move the aircraft, and then you need somebody to sell the aircraft for you. In some instances, the aircraft were parked and getting ready to start a major inspection, and we had to raise the capital to complete the inspection before the aircraft could be sold. Since I am not an aircraft broker, we had to hire an aircraft broker who could market and sell the aircraft, take pictures of them, list them, and do all of those things necessary. In the meantime, we were working through all of the title issues and liens that were attached to the aircraft.

Applegate: I think that the one distinction between this case and the Avantair matter is that at Avantair, when we sold (the airplanes), we sold them through the bankruptcy court, and we obtained a court order which was filed with the FAA registry that extinguished any liens or encumbrances that were attached to the aircraft, whereas here we didn’t have to have that, and so we had to deal with each of the lien holders who often surfaced after we had sold the aircraft and make sure that the title was clear for the next owner that was taking over the aircraft. Unfortunately, in this case, some of the lienholders did not follow federal law, and it took some time to resolve the liens that had been attached to the aircraft that were invalid.

Applegate: For the 14 owner groups that I represented, they have all been sold.

Applegate: It started around Memorial Day weekend, the end of May, and we had the first one sold on June 9, 2023. So, it was just two or three weeks to sell the first one, and then the last one sold in mid-December. Several of the aircraft had been parked to start major inspections, so those that had to complete a major inspection before being sold took longer to sell. We also had one aircraft where the engines were off the aircraft because they were undergoing an overhaul, so we had to wait for the engines to come back before we could sell that aircraft.

READ: 16 reasons to charter flight-by-flight

Applegate: With Avantair, it was the first time it had ever happened. There were just a lot more unknowns. This time, when it happened, I felt like I had a playbook that I could go to. When someone would ask me a question that said something like, ‘Should I keep paying my management fees to Jet It?’ Last time, I was looking through the contract and looking for guidance, and this time, I sort of had an answer, ‘Absolutely do not pay Jet It anything else ever unless ordered by a court to do so.’ I was pretty confident in those statements. I think that was a difference.

Applegate: I think the major difference is that Avantair continued to fly a lot longer when they had run out of money. As a result, the aircraft had a lot more encumbrances on them. Additionally, you had people who were not transparent in their desires to help the process along, meaning that they would not release the aircraft or the engines or parts and kept them for themselves.

I think that was because a lot of service providers weren’t supporting the Avantair aircraft any longer because of lack of payment, and Avantair had to go down and start dealing with some less reputable people to continue to fly. Then, of course, in that matter, they had what I call donor aircraft. Avantair would use parts from two or three aircraft in the fleet to keep the rest of the fleet flying, and you didn’t have that (with Jet It). What you had here was that the aircraft were grounded. Many of the aircraft were already not flying because they had finished inspections that hadn’t been paid for or were scheduled to start a major inspection, and the deposit for that inspection had not been paid, so you certainly had an instance where those unpaid inspections needed to be paid for, but you didn’t have the aircraft in such bad shape.

When we went to sell these 14 aircraft out of Jet It, they were relatively in good shape. They were maintained and current for the most part. We did not have huge invoices of things that had to be fixed on them before they were sold. I think those were all positives, and the process was much faster because we stayed out of bankruptcy. We did not have to go to bankruptcy court for approval to sell the aircraft, so that saved time and legal fees. We did not have to wait for the judge to process the orders and approve the sale to the third-party providers that we found, and we did not have to have an attorney attend all of the bankruptcy hearings. Jet It was a much quicker process. Avantair’s bankruptcy was open for two years, and here we sole the 14 aircraft I was involved within six months.

Applegate: I don’t know. Certainly, any of the creditors could have put Jet It in bankruptcy, and then really, any other fractional owners could have done it, or Jet It itself could have put itself in bankruptcy, but no one ever filed for bankruptcy. I guess for a variety of reasons, but maybe they just understood that it would make things more expensive and slower, I suppose. That’s not to say it still couldn’t happen. You could still have a filing, I guess, at this point.

Applegate: There’s a six-month clawback in bankruptcies. However, I think it would be hard to claw back any of the aircraft sales that Jet It did not own an interest in. When Jet It ceased operations, one of the first things we did and understood to do because of Avantair was to buy out all of the Jet It shares. We pooled money from the co-owners, or one of the co-owners volunteered to front that money, and we took away the ownership interest that Jet It had in any of the aircraft I was involved with. If there was a bankruptcy filing now, the court would look at any transactions that occurred within the last six months to see if what we paid Jet It was fair market value. I think in every instance, we paid more for the shares that we immediately purchased than we ended up selling the aircraft for after expenses, so I don’t think there would be any reason for the court to do a clawback.

READ: Caveat Emptor: Avoiding private jet scams, bankruptcies, and shutdowns

Applegate: Hindsight is 2020, but if any of the Avantair co-owners had done just a visual or an audit, it would’ve been very apparent that their aircraft was never going to fly again. If you’re a prospective fractional owner looking at some of the newer programs that are out there or where no financial information on the company is available, one of the things I think any of the program providers would allow is the right to audit and the right to do a visual inspection, say, once a year or every six months or whatever you want to do. I think that’s one thing you can do.

Additionally, you certainly can obtain a title report at any time. For $100 dollars, you can get a title report and make sure that there are no encumbrances that have been attached to the aircraft. That’s one thing that you could do annually which is a good indicator if the company is having problems.

I would also think, as the owner of the aircraft, you would have the right to make sure that the maintenance programs on the aircraft are current and not in default, as we had in the Jet It matters.

I think most fractional owners are fractional owners because they do not want to deal with the nuts and bolts of owning a whole aircraft. However, you don’t need to be an aircraft expert to do a visual inspection or order a title report.

Also, a fractional owner could hire somebody to spend a day and go in and just make sure that the aircraft is being maintained in the way it should and that it has all its parts on it. It doesn’t have to be a deep dive. I think if any of those things would’ve occurred in Avantair, we would’ve understood that that fleet needed to be perhaps grounded well before it was.

Not that I know of. It would have been easy to learn that the programs on the aircraft were in default.

Applegate: I don’t think anybody contacted me because they were unhappy, but in December of the previous year, I had an owner who was looking to acquire an additional share in another aircraft with Jet It. I had helped him buy his first share with Jet It. When I went into the FAA records to look at what he owned, he had been placed on a different aircraft that he was contracted to purchase. That raised some red flags for me. I went ahead at that time in December and pulled title searches for all my clients who had shares with Jet It and really didn’t find anything. There were a couple of small fuel liens that had been placed, but all of them had been paid and released, and there was really no indication of any issues at that time in December.

Applegate: My clients who had Jet It shares had some language that if there was a cease of operations or bankruptcy, they would be immediately put in contact with the other co-owners so that they could do something, which is something I wish I would have had when I worked on the Avantair matter. We also added language that said that the aircraft itself would not be considered part of the bankruptcy estate if there was a bankruptcy.

We did try to proactively add some things that I think are important in the companies that are out there that are just starting up and haven’t really gotten their feet underneath them yet. We also recommend that the right to audit be included, if not in the form of documents the fractional company provides. Finally, the contract should state that in the event the management company (fractional provider) ceases operations, the co-owners agree to sell the aircraft.

Applegate: When my clients came to me, and they had selected Jet It as their provider, we would have a conversation immediately, and I would give them my opinion and my history of how difficult it is for startup fractionals to be successful. In particular, if there are flaws in the business model that I think are not sustainable, then I flag those items to them as well. At the end of the day, it’s really the client’s choice as to what their risk tolerance is. When I do have clients who want to join programs that maybe I’m not as comfortable with, then what we do is try to get as much protection in the contract itself as we can.

Applegate: I don’t think they really understood the risks they were taking by entering into the program, but in hindsight, certainly having dealt with 120 or so of these co-owners, what they quickly realized is when they went to find a replacement program, there was no other program priced in the manner in which this one was, which was a telltale sign. It’s very difficult to have a program, for example, that has fuel fixed. Fuel is the variable that you can’t control, and so if you’re going to fix fuel, you’re taking, as the operator, taking on a whole lot of risks that you can’t control. Those are the types of things that when my firm is looking at a program for a client, we point those risks out and say, ‘I’m not sure these things make this a sustainable program.’ It is also very difficult for a start up company to be a national service provider. They are more likely to be successful if they start out as a regional provider where the owners are in one region of the country until the fleet is large enough to handle the entire country.

Applegate: There are some clients that take our recommendation and go with a more established program. However, there are some clients who will say, ‘I understand the risk, but if I can continue with this program for one or two years, then it’ll be well worth it for me,’ which is fine. They’ve understood the risk and decided to take the risk. I think that’s very different than somebody who doesn’t have a consultant or an aviation attorney and doesn’t understand the risk. Then they’re really shocked when the program doesn’t last and ends up in some circumstance where all of a sudden, you own a plane with nine or 10 people you don’t know. That’s a very uncomfortable situation for most people.

Applegate: I don’t know the answer to that question. I certainly only had maybe 10 clients who had bought shares with Jet It, but I’m just one of several people out there who could have done this service for them. I do know from my time when I was in-house counsel at NetJets that I would say, at that time, less than half of the people had somebody reviewing the contract for them who had any type of aviation experience. I don’t know if that has changed because that was a long time ago. Fractional contracts are complex and long – over 50 pages. It is a good idea to have somebody to look at it who’s read it before and can explain the purpose of each document and the important program points.

Applegate: I think if you look at the purchase price themselves, they, in general, sold at wholesale prices instead of retail prices. You have to remember that some of these people had just bought in a year ago, and so not everyone had the same amount of time as owners. As a result, those who bought in most recently saw the largest decline in value, whereas other co-owners who owned longer expected some depreciation.

The other thing you have to factor in is all of the amounts that had to be paid to vendors. Even if the (sale) price was a wholesale value after deducting what was owned on the aircraft, the proceeds to each co-owner were greatly diminished. However, most co-owners were willing to take offers that were below market to get the aircraft sold. By selling, you get that closure and can move on to the next private aviation solution.

READ: A Beginner’s Guide to Buying A Private Jet

Applegate: I had people who contacted me (after JetSuite’s bankruptcy, which cost jet card holders $50 million) to see what they could do to get their money back. I said, ‘You’re an unsecured creditor and way down the list, and there’s nothing you can do.’ I wasn’t going to take on those clients and charge them legal fees when I didn’t think there was a chance for any type of recovery.

Applegate: If you are a jet card holder, you basically have given someone money to perform services in the future, which makes you an unsecured creditor if you ever want to try to get that money back in the event of bankruptcy or if they cease doing business. I don’t know a lot of programs, if any, that segregate that money so that they can’t use it for other things. The chances of that money just sitting in an account at the time a company ceases to do business or files for bankruptcy are pretty low.

(Jet cards are) less money. You’re only giving them a couple of hundred thousand versus when you buy a fractional, that’s usually over half a million. While it’s emotionally taxing to say goodbye to the money that you’ve given to a jet card program, it’s sort of done. ‘Okay, my money’s lost,’ and you move on.

Whereas if you’re entangled in a fractional program that ceases to do business or files for bankruptcy, you’re in it for the long haul. You have to participate in these owner groups, and you have to make decisions. You have to fund the legal fees; you have to fund to get the aircraft moved. Maybe you’ve got to pay the inspection facility some money in order to move it to a tax-friendly location to get it closed. You’re going to be coming out of pocket knowing that there’ll be a return eventually when the aircraft sells. I’m always sending these emails, and it’s like I’m reminding them of this bad decision that they made to enter into this program. I’m the least popular person. Often, I’m asking for more money. We need more money for this.

The entanglement that’s involved in fractional ownership is more, but if you hire someone to handle it, then maybe it’s just a matter of voting on a few things every month and then waiting until your check comes and fronting some money. As long as you’ve got somebody managing the unwinding for you, then perhaps it’s not as terrible as it sounds.

READ: What happens to your jet card and private jet membership deposits?

Applegate: I think some of the fractional programs will allow that money to go into an escrow account versus going directly to the providers. I think that’s one thing that you can do. If they don’t allow that, maybe you ask why.

Applegate: It’s a hugely capital-intensive endeavor because if the fractional provider is ordering aircraft from the manufacturer for new deliveries, they have to put down deposits similar in size to what you would have to put down if you were ordering an aircraft yourself. The manufacturers don’t make a lot of concessions and lower those deposit requirements. Because it’s so capital-intensive, I think it’s difficult to launch a fractional program unless you’ve got some deep-pocket investor behind you, or maybe you’ve gone public, or whatever the case is, but it’s very difficult to launch at first.

Applegate: I would say to get proposals from a couple of different companies, and if one is ridiculously lower than the rest of them, then I think it’s maybe too good to be true.

Then, you assess your risk tolerance. If it is priced so low that it can’t be sustained, is that okay as long as they’re around for the next two or three years?

If you get the presentations and the documents, and you can’t understand the program or the contracts do not match what you were sold, that might be a red flag as well. Why is it that they can’t explain what’s happening in a manner that makes sense, or when they send you their pro forma spreadsheets to show you, at the end of the day, you’re going to make money by running these fractional shares or something like that, just do a gut check to know, and make sure that that makes sense.

Then, it’s a very small industry, so it is probably the case that someone knows a bit about whatever company that you’re considering. Just seek those consultants or those attorneys out to get an opinion on them before you sign up. Even if you continue to do it, and there are some risks, at least you’ve done it in an informed way so that you’re not surprised in a couple of years when it does all not work out exactly how you thought it would.

READ: You’re fired! Are you an unprofitable private jet flyer?