New and veteran private jet flyers have discovered that if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. Here are some of the sad stories we’ve covered in the past five years.

Summerset Maugham once wrote about the French Riveria as “a sunny place for shady people.” While private aviation has a lot of great people, and I enjoy covering the industry, I have to admit I was surprised that, looking back over the past five years, there have been over a dozen private jet scams, bankruptcies, and shutdowns. To me, that seems like too many.

It’s also important to note not all of the shutdowns and bankruptcies in the private jet flight provider sector have involved fraud.

When people ask me about the private jet business, I say think about the big airlines.

But instead of scheduling routes and flights six months in advance, your customers create your schedule as little as 24 hours before departure.

Bismarck, North Dakota to Biloxi, Mississippi, no problem.

Tough business or not, the failures cost customers tens of millions of dollars.

Here are some of the ones we’ve covered and the lessons learned.

Was the French hotel giant with over 30 brands and 200,000 employees jumping into the private jet arena?

The press release reads, “AccorJets, Europe’s largest fractional ownership operator, has introduced a by-the-day-based program for the Gulfstream G650 and Praetor 600. The move is designed to give greater flexibility to shareholders of the ultra-long-range business jet and help boost the company’s share of the high-end private jet travel market.”

The website generously used images of Flexjet aircraft. A representative quickly responded there was no connection.

I reached out to the PR for Accor. It was news to him, but it’s a big company.

A few days later, he confirmed despite listing the Accor CEO and its headquarters address on its website; there was no connection. “After consulting with our operations team, it looks like (AccorJets) is not a legitimate program, and it is not associated with Accor. Our legal team is currently investigating the matter,” he told me.

A week later, the Accor Jets website was gone.

Lesson: Anybody can create a website, make business claims, and start soliciting customers. Like scam emails meant to trick you into thinking that they are coming from a bank, Amazon, etc., having a nice website does not equal a credible business.

Ascension Air’s CEO, Jamail Larkins, was a rising star in business aviation and beyond.

In 2000, the FAA named Larkins the national spokesman for its Young Eagles program. He was featured in Inc. magazine in an article titled “Aerospace Mogul In The Making.”

The Atlanta-based operator of Eclipse 550 and Cirrus SR22 aircraft was selling fractional shares and jet cards.

But there were problems.

In April 2019, we wrote about Randall F. Hafer. The Atlanta lawyer signed on to buy a share in N927CS in 2013.

He says as his term was expiring in 2017, he became concerned that there was no news of his SR22 being sold.

He claimed Larkins told him that he had three new SR22s on order from Cirrus, yet Ascension would cancel his flights on short notice, citing mechanicals.

Frustrated, he told Larkins to stop charging him the monthly management fee. He said it continued for another month before stopping, and while Larkins promised him a refund, he never received it.

Then came a big shock. In accessing FAA records, Hafer says he was surprised to learn Larkins had registered Ascension as the singular owner of his SR22 instead of listing the fractional shareholders.

He also says the airplane was used as collateral for a loan.

An executive with Aero Specialty Finance, LLC said the company did make a loan to Ascension Air Management, Inc. in April 2018, on three Cirrus aircraft.

The tail numbers were N928CS, N941CS, and N927CS. He declined to specify the amount of the loan but said it was based on the belief that Ascension was the rightful owner of the airplanes being used as collateral.

A month later, the website was down, and Ascension was gone. When I last checked in 2020, one of the SR22s was being auctioned by the bankruptcy court.

Lesson: Favorable media coverage doesn’t mean a viable business. Most of all, verify documentation and check from time to time. Trust but verify.

Start-up Climb leaned heavily on the founder’s connection to legendary aviation entrepreneur David Neeleman and counted two of the JetBlue founder’s siblings on his board.

Started by Brandon Solomon, who says he met the airline guru at a wedding, the company planned a Pilatus PC-12 member program.

It launched in January, and by April of this year, Climb was offline.

Solomon said he couldn’t source sufficient lift, and members were refunded unused membership fees. However, he planned to relaunch.

In August, Solomon told us, “At this time, there are no plans to restart operations at Climb.”

Lesson: Beware the use of big-name backers. These backers – who provide credibility for start-ups, don’t necessarily have investments with their own money, and they have limited involvement in the business.

JetSuite certainly seemed like it was positioned to challenge the leaders in private aviation.

It had moved into the 20 largest charter operators.

Its Founder and CEO, Alex Wilcox, has an impeccable pedigree.

He cut his teeth at Virgin Atlantic Airways under Richard Branson and David Tait.

He was part of JetBlue’s launch team. Later he was COO of India’s Kingfisher Airlines.

It also had staying power, having launched in 2009 during the Great Recession.

JetSuite had expanded beyond its West Coast niche and Phenom 100 fleet to add Citation CJ3s and Phenom 300s.

It had attracted investment from JetBlue and Qatar Airways. It also launched the by-the-seat private airline JSX, which is still flying – and expanding today.

Then came Covid, and JetSuite quickly grounded its fleet. A trip through Chapter 11 was next.

SuiteKey customers lost $50 million in deposits. Some said they hadn’t realized that their funds were used as operating cash, although it was clear from reading the contracts.

Moreover, many were surprised that the company never gained real profitability. It was prolific in raising money, but so were its losses.

When it filed for bankruptcy, it had less than $1 million in cash.

Lesson: Don’t bank on positive coverage in the media, and don’t count on big investors to bail you out.

In November 2017, ImagineAir announced plans to double its 14 single-engine Cirrus SR22 aircraft fleet.

It ranked 399th in the 2015 Inc. 5000 list.

Then CEO Benjamin Hamilton, a co-founder, said revenues grew 980% in three years.

However, in May 2018, members received an email stating, “It is with great regret that the Board of ImagineAir and the company’s leadership announce the suspension of operations effective 11 pm ET, May 24, 2018.”

It continued, “While the potential of ImagineAir never dimmed, the company’s leadership and advisors were unable to secure the necessary short-term funding to continue operations, nor the long-term funding to scale the company to profitable scale.”

By the end of the year, Chapter 7 bankruptcy proceedings were underway.

Lesson: Track previous growth promises to actualization. It can be a warning sign when expansion plans consistently don’t come to fruition.

In 2019, we reported on the arrest of jet card broker Tomer (Tom) Osovitzki.

His company Jetlux had been named in a 2018 lawsuit by charter operator Silver Air suing Kim and Khloe Kardashian for $225,353 in unpaid charter bills.

According to charges brought by the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, “As alleged, Tomer Osovitzki manipulated the approval system for credit cards to push charges through that he knew were unauthorized and would have been declined. Additionally, Osovitzki allegedly used his clients’ credit card account information to make unapproved charges. Now, Osovitzki and his company are grounded, and he must answer for his crimes.”

The government alleged $1.3 million in fraudulent charges between 2017 and 2019.

In August of this year, JetLux, Inc., with Osovitzki listed, filed with the State of Florida to reinstate itself as an active business.

Lesson: Google is your friend. Find out who owns the company before you wire money – or provide your credit card information.

Paul A. Svensen Jr. founded JetCard Plus after his previous company, Jet Network LLC, where he was COO, went into bankruptcy.

His profile billed him as a “pioneer” in the jet card industry, citing appearances on “CNBC, CBS MarketWatch, ABC News, and Good Morning America.”

In May 2019, a Florida court ordered JetCard Plus Inc. of Miami to pay $219,692 to Steven T. Mnuchin Inc.

Yes, that is Steve Mnuchin, the former Treasury Secretary.

In seeking to get his money back, Mnuchin alleged money transfers between JetCard Plus and New York-based broker Uber Jets.

In a January 2020 court filing, Mnuchin’s lawyers wrote, “UberJets is owned by Paul M. Svensen, the son of JetCard’s founder and former executive Paul A. Svensen Jr…Bank records obtained by STM (Mnuchin) show significant monetary transfers from JetCard to UberJets and Paul M. Svensen. STM has been unable to obtain any evidence showing that the transfers served legitimate business purposes.”

However, in May 2021, Mnuchin asked the court to “dismiss with prejudice his action against UberJets, LLC, Paul M. Svensen, and Paul A. Svensen, Jr.”

It continued, “Based on discovery in this action, STM is aware of no evidence of common or shared ownership between or involving UberJets LLC, on the one hand, and JetCard Plus Inc, a Florida corporation, and Paul A. Svensen Jr., on the other.”

UberJets continues, while JetCard Plus appears to be long gone.

Lesson: We go back to Google search. Make sure you know with whom you are doing business so you can make decisions with facts.

European VLJ operator Wijet, like other failures, touted partnerships with well-known, credible players, in its case, American Express and Air France.

In the case of the French national airline, it continued its partnership even after Wijet shut its U.K. subsidiary Blink Jet in 2018, leaving jet card customers high and dry.

Air France seemingly had no issues as Wijet continued to tout the relationship on its website until it finally shut down its French operations over a year later in December 2019.

Along the way was an order to buy 16 HondaJets and promises its fleet would grow to 50 airplanes.

Its website was put up for sale by liquidators in January 2020.

Last we heard in 2021; its principal was being investigated for fraud.

During the turmoil, several Wijet customers told me they figured if Air France was still on its website (and vice versa),

Lesson: Judge providers on their own merits, not for the company they keep.

Yes, there were others. For example, Zetta Jet, which left up to $100 million in unpaid bills, was flying high until it wasn’t.

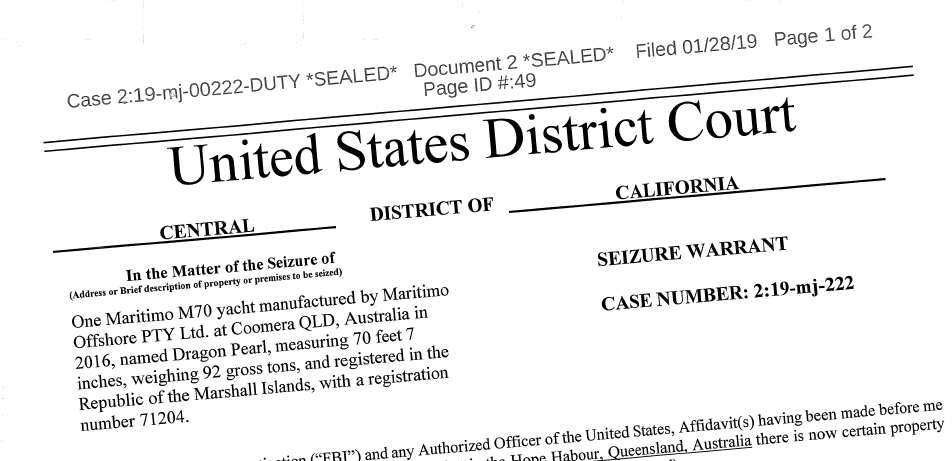

Its former boss, Geoffrey Cassidy, was recently charged with embezzlement in Singapore. He allegedly used company funds to buy a yacht for personal use.

A report on the company found that it was “insolvent almost from inception.”

Yes, you can protect yourself by ensuring your provider has an escrow account, but not many do. It can also be a hassle.

No, the chances of you losing six figures is relatively low.

Yes, I agree with some subscribers who tell me there’s no silver bullet.

The contracts you sign are written (and updated) for the provider’s benefit. See JetSmarter.

You can mitigate risk by chartering flight-by-flight. However, that takes your time, pricing each trip, reading contracts, which can vary between quotes, and so forth.

My best advice is to make sure you do your due diligence as best you can.

Few players are publicly traded or have a significant amount of financial data in the public realm.

Try to speak to other current and former customers if you can. It also makes sense to have a lawyer review the contract.

Nice websites, adoring articles, and well-known backers are marketing tools not to be confused with profits or success.

And remember Oxford defines caveat emptor as “the principle that the buyer alone is responsible for checking the quality and suitability of goods before a purchase is made.”